5

Orderly exit: recovery and resolvability

5.1

The PRA’s approach to new and growing bank supervision aims to facilitate competition, in support of its secondary competition objective. Competitive markets involve firms being able to enter and exit. The PRA’s aim is not to avoid all instances of failure, but instead to work with firms and the Bank as resolution authority to make sure that banks progress from being a new and growing bank to becoming an established bank that would be able, if necessary, to exit in an orderly manner. This means without disruption to the financial system, interruption to the provision of critical functions or exposing public funds to loss. The orderly failure of a new or growing bank at an early stage of its life is likely to have no or minimal impact on financial stability, and is a natural part of a competitive economy.

- 15/04/2021

5.2

The likelihood of failure is higher during the early years of a bank’s development.[60] Factors which may lead new and growing banks to fail include failure to obtain the required loss absorbing capacity or an inability to realise their business model. Many new and growing banks operate in highly competitive markets and many have novel and untested business plans; this facilitates innovation and competition but not all may prove to be viable. Coupled with this, new and growing banks may have fewer recovery options available to them than established banks, meaning it is crucial they have the ability to exit the market in an orderly way, if required.

Footnotes

- 60. This is common across industries, see for example P.A. Geroski, What do we know about entry?, International Journal of Industrial Organization 13 (1995) 421-441, or Kücher et al, Firm age dynamics and causes of corporate bankruptcy: age dependent explanations for business failure, Review of Managerial Science (2020) 14:633-661.

- 15/04/2021

5.3

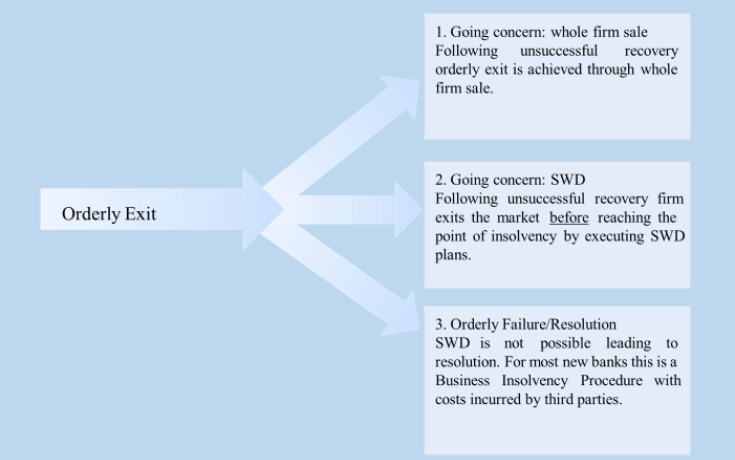

Orderly exit is the overarching term for banks that no longer have a viable business model and that need to exit the market following unsuccessful attempts to recover. The exit options include going concern and resolution routes. Going concern routes refer to the actions the bank may be able to take to facilitate its own exit from the market. These firm led actions include selling the firm as a whole or winding down the firm as a whole while maintaining solvency throughout to the point it can be liquidated safely, repaying all depositors and creditors in full. Resolution routes refer to the firm’s entry into the resolution regime.[61] Box 3 provides an overview.

Footnotes

- 61. Entry into the resolution regime is triggered if a bank is judged by the PRA to be failing or likely to fail and by the Bank of England that it is not reasonably likely, having regard to timing and other circumstances, action will be taken that will result in the firm no longer failing or likely to fail.

- 15/04/2021

Recovery plans

5.4

New and growing banks should have credible recovery plans which are sufficiently detailed and practical to ensure they reflect the complexity and size of the firm and would be useable in a stress. Recovery plans are important for all firms; for new and growing banks which may have additional vulnerabilities to stress, a robust recovery plan ensures the bank is aware of the range of recovery options available, the impacts and limitations of these actions, and ensures that management actions can be undertaken in a timely manner. However, the PRA recognises new banks have a more limited range of recovery options.

- 15/04/2021

5.5

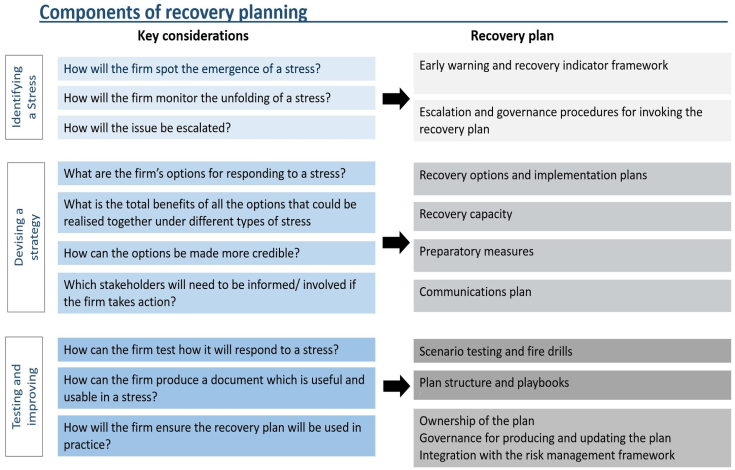

The PRA has observed that recovery plans produced by many new and growing banks can initially be unrealistic and would not be useful in a stress. Boards of new and growing banks should ensure the bank’s recovery plan is relevant, credible, and executable in a severe stress. Banks should consider the components of recovery planning shown in the chart below, and ensure these are covered in their recovery plan, as well as consulting PRA recovery planning Policy. [62]

Footnotes

- 62. See SS 9/17 for more information on recovery planning

- 15/04/2021

Figure 2: Components of recovery planning

- 15/04/2021

Solvent wind down (SWD)

5.6

SWD is a way for firms to exit the market in an orderly way, by winding down their business in its entirety to the point it can be liquidated safely, repaying all depositors and creditors in full. For a new or growing bank experiencing a stress, entering SWD may effectively be the final going concern option before resolution.

- 15/04/2021

5.7

The board of the bank is responsible for deciding whether to enter a wind down and for ensuring the firm maintains its solvency during implementation. The PRA expects banks to engage with their supervision team at an early stage if they are considering enacting their SWD plan.

- 15/04/2021

5.8

As explained in Chapter 4, the PRA buffer for new and growing banks has not been calibrated to provide sufficient capital for banks to enact a SWD. As part of their forward capital planning, banks should understand the constraints on the feasibility of SWD as an action. If a SWD is not possible, or if an attempted SWD is likely to fail, the Bank and the PRA will assess whether the bank would meet the conditions to be placed into resolution, as described below.

- 15/04/2021

5.9

The PRA expects new banks to have a board approved SWD plan in place at the point of authorisation (or exit from mobilisation). New and growing banks should maintain their SWD plans, regularly updating them to ensure they remain appropriate as the business develops. These plans should identify clear triggers for their timely implementation to ensure solvency can be maintained throughout the wind down. Banks should maintain SWD plans. All SWD plans, regardless of bank size, should follow the principles outlined in Box 2. It may be appropriate for the SWD plan to form part of the bank’s recovery plan, though boards should consider whether factors such as the size of the bank or emerging threats to sustainability mean a separate SWD plan is more appropriate.

- 15/04/2021

5.10

The PRA may review banks’ SWD plans at its discretion, especially if the bank is experiencing, or likely to experience, a stress or has insufficient financial resources. The PRA may seek external assurance on the validity of the SWD plan, particularly if there is a reasonable chance the bank will need to implement its plan.

- 15/04/2021

Box 2: SWD plans - overview:

SWD plans should be:

- Credible, with a realistic prospect of effective implementation and demonstrating how the firm will meet minimum regulatory requirements throughout.

- SWD plans must demonstrate that the business can be wound down in its entirety to the point it can be liquidated safely, repaying all depositors and creditors in full.

- Specific, with actions built around the specific business model, operating cost and contractual obligations of the firm.

- Measurable, with clear timelines for delivery and a framework for identifying divergences from plan.

- Sufficiently granular with detailed projections of the financial and non-financial resources needed to implement the plan and maintain solvency throughout.

- Open, with a clear assessment of the key assumptions made and a sensitivity analysis of those assumptions, including analysis of wind down under different scenarios.

- Risk-aware, with an identification of the key risks to delivery and contingency plans to mitigate those risks, including a communication strategy.

- Adaptable, with consideration of alternative wind down scenarios where possible, including consideration of stressed market conditions, and the ability to be updated and refreshed in an appropriate timeframe as the business grows.

- Clearly owned, with an identification of individual accountability for delivery.

- Board-approved, with a demonstration of appropriate challenge given prior to their approval.

- Closely linked with the recovery plan and with the ICAAP, with clear board approved triggers for when the SWD plan would be initiated.

- 15/04/2021

Resolution

5.11

A series of conditions must be met before a bank may be placed into resolution (together, the resolution conditions). The first two resolution conditions are most relevant to new and growing banks. First, the bank must be deemed ‘failing or likely to fail’. This includes where a bank is failing or likely to fail to meet its threshold conditions in a manner that would justify the withdrawal or variations of authorisation.[63] This assessment is made by the PRA. The second condition is that it must not be reasonably likely that action will be taken – outside resolution – that will result in the bank no longer failing or being likely to fail. Such actions could include the bank’s recovery actions. This assessment is made by the Bank, as resolution authority, having consulted the PRA, FCA and HM Treasury. The conditions for entry into the regime are designed to strike a balance between, on the one hand, avoiding placing a bank into resolution before all realistic options for a private sector solution have been exhausted and, on the other, reducing the chances of an orderly resolution by waiting until it is technically insolvent.

Footnotes

- 63. The ‘threshold conditions’ include that the bank must have: adequate resources to satisfy applicable capital and liquidity requirements; appropriate resources to measure, monitor and manage risk; and fit and proper management who conduct business prudently – see Part 4A and Schedule 6 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2013/9780111533802.

- 15/04/2021

5.12

The Bank sets preferred resolution strategies for all banks. For smaller banks that do not supply transactional accounts or other critical functions to a scale likely to justify the use of resolution tools, the preferred resolution strategy is the applicable insolvency procedure. Usually, this is the Bank Insolvency Procedure (BIP).[64] Under this, the bank’s business and assets are sold or wound up after covered depositors have been paid by the Financial Service Compensation Scheme (FSCS) or had their account transferred by the liquidator to another institution using FSCS funds. BIP is likely to be the preferred resolution strategy for most new and growing banks.

Footnotes

- 64. Or other modified insolvency procedures depending on the type of firm, i.e. the building society insolvency procedure (BSIP) for building societies or the special administration regime (SAR) for investment firms. In some specific circumstances, and if a firm does not hold FSCS covered deposits, a corporate insolvency may be more appropriate.

- 15/04/2021

5.13

In order to support orderly resolution, banks must maintain a single customer view and exclusions file, [65] and are required to provide this to the PRA or FSCS within 24 hours of a request.[66] Banks’ systems must automatically identify the amount of covered deposits payable to each depositor and identify any portion of an eligible deposit that is over the specified coverage level.[67]

Footnotes

- 65. The exclusions file that firms are required to provide should include data on deposits which are not in the SCV including for example deposits held in client accounts and deposit aggregators.

- 66. Depositor Protection Part of the Rulebook.

- 67. Depositor Protection Part of the Rulebook (4.2).

- 15/04/2021

5.14

As a bank grows, the Bank can change its preferred resolution strategy to either a partial transfer or a bail-in resolution strategy. Banks should be aware of the PRA’s and the Bank’s Resolvability Assessment Framework (RAF) and, as part of their forward planning, anticipate when their preferred resolution strategy may change and when they will come into scope of different policies, for example the MREL[68] or operational continuity in resolution (OCIR).[69] [70] Banks should plan for this well in advance and consider how they will transition to meet these policies.

Footnotes

- 68. June 2018: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/paper/2018/boes-approach-to-setting-mrel-2018.

- 69. Policy Statement 21/16 ‘Ensuring operational continuity in resolution’, July 2016: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2014/ensuring-operational-continuity-in-resolution.

- 70. Operational Continuity Part of the PRA Rulebook: http://www.prarulebook.co.uk/rulebook/Content/Part/320890/24-06-2020.

- 15/04/2021

Box 3: Orderly Exit Options

- 15/04/2021